From Entanglement to Topology: Tracing the Quantum Evolution Toward Robust Computation

- hashtagworld

- Aug 20, 2025

- 6 min read

A comprehensive chronicle of quantum computing’s historical milestones and how a new topological breakthrough (zero modes in many-body Kondo lattices) addresses deep-rooted challenges in quantum hardware.

Introduction: Where Quantum Futures Begin

In the early decades of the 20th century, quantum theory emerged not as a refined extension of classical physics but as a radical rupture. Planck’s quantization, Einstein’s photoelectric effect, and Schrödinger’s wave mechanics offered a framework that defied intuition where particles could behave like waves, superposition prevailed, and entanglement rendered spatial separation meaningless.

Yet it took nearly a century for the theoretical peculiarities of quantum mechanics to converge with the practical realm of computation. The journey from atoms to algorithms has redefined what machines can know and how they can learn. At the edge of this evolution, a new frontier emerges: topologically protected many-body quantum states.

Theoretical Origins: Seeds of the Quantum Machine

In the 1980s, the conceptual groundwork for quantum computing was laid. Paul Benioff (1980) proposed the quantum Turing machine, showing that computation could be modeled using quantum mechanics. Richard Feynman (1981) argued that quantum systems could not be efficiently simulated by classical computers, introducing the idea of the quantum simulator.

David Deutsch (1985) advanced the notion of a universal quantum computer a theoretical machine capable of simulating any physical system. Quantum mechanics thus evolved from a theory describing the microscopic world to a framework for information processing itself.

These ideas introduced a compelling notion: in a world where nature computes quantumly, machines must follow suit. Yet realizing this vision required new rules, architectures, and aspirations.

Algorithmic Breakthroughs: Proof of Power

The 1990s were a decade of proof. Peter Shor’s 1994 factoring algorithm demonstrated exponential speed-up over classical methods. Grover’s 1996 search algorithm enabled quadratic acceleration in unstructured data queries.

These breakthroughs validated quantum computing as more than an academic curiosity it became a field with real-world consequences. But the inherent fragility of quantum systems posed a problem. Quantum error correction became indispensable, prompting the development of the first codes by Shor and Steane to stabilize computations.

The question, however, remained: could we build a quantum computer before decoherence rendered it useless?

Experimental Transition: From Laboratory to Prototype

Between 2000 and 2015, momentum shifted from theory to engineering. Researchers began constructing physical qubits using trapped ions, superconducting circuits, and photonic gates. IBM implemented a basic version of Shor’s algorithm using NMR technology. Google, Intel, and other industry leaders raced to build scalable qubit arrays.

However, noise, instability, and scaling limitations hindered progress. The NISQ era emerged Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum systems. These machines, though error-prone, could outperform classical devices on niche tasks. Google’s 2019 Sycamore processor, claiming “quantum supremacy,” attracted both excitement and criticism.

What became evident: achieving quantum advantage required not just qubits but robust qubits.

The Hardware Bottleneck: Why Robustness Is Essential

Quantum error correction is vital but costly. Building logical qubits resilient against decoherence requires many physical qubits. IBM’s roadmap targets 200+ logical qubits by 2029, necessitating thousands of physical ones.

Is there an alternative path? Can qubits be made inherently robust, embedding error correction into the physical substrate itself?

Topological quantum computing offers such a promise. When information is encoded in the system’s global (topological) rather than local properties, it becomes immune to small disturbances. Microsoft’s pursuit of Majorana fermions is a leading example. Yet such systems often rely on rare materials and delicate environments.

The question persisted: How can we build accessible, robust, and scalable quantum hardware?

A New Chapter: Topological Zero Modes in Kondo Lattices

In March 2025, physicists Claudio Lippo, Alexandre Dauphin, Raffaele Marino, and Maciej Lewenstein published a groundbreaking study in Physical Review Letters introducing a novel topological approach to robust quantum information encoding. Their research proposed the use of magnetic many-body interactions to generate topological zero modes in engineered Kondo lattices. This marks a departure from prior reliance on fragile ingredients like Majorana fermions or fine-tuned spin-orbit couplings.

At the heart of their model lies a tailored 1D Kondo lattice, combining itinerant electrons with localized magnetic moments. Through a sophisticated combination of hopping terms and Kondo exchange couplings, the team engineered a Hamiltonian exhibiting nontrivial many-body topology, leading to the emergence of four-fold degenerate ground states in the thermodynamic limit. Numerical simulations on systems up to 60 sites (including both conduction and Kondo spins) revealed a striking phenomenon: edge magnetization of ±½ in the ground states, directly signaling the presence of topologically protected zero modes.

However, the challenge of verifying these topological features in finite-size systems was non-trivial. Due to strong finite-size effects, the zero modes did not always appear exactly at zero energy. To overcome this, the researchers introduced a new diagnostic method: correlation matrix pumping. This technique analyzes the spectral flow of the single-particle correlation matrix across an adiabatically modulated boundary condition, allowing direct extraction of many-body topological invariants from exact ground states. This leap goes beyond single-particle topological theory and operates even in the presence of strong interactions and disorder.

The authors further reinforced their findings with effective Hamiltonian analysis, demonstrating how localized edge modes arise from higher-order hopping and Kondo coupling structures within the lattice’s periodic unit cells. Importantly, the model’s block-diagonal structure and periodicity of four sites enabled tractable self-energy computations that confirmed the stability of the zero modes across a wide parameter space.

This approach not only bypasses the limitations of exotic quasiparticle engineering but grounds topological protection in ubiquitous physical interactions specifically, in the quantum magnetism already present in many solid-state systems. In doing so, it paves a path toward intrinsically robust quantum hardware, where error-resilience is not imposed externally but emerges from the system’s native structure.

Fig. 1 : (a) Schematic of the Kondo lattice model Eq. (1), where the electronic sites (blue) have a uniform hopping t between them. Kondo spins (red) are coupled to some of the electronic sites with strength Jₖ. Panels (b),(c) show the spectral function featuring the zero edge modes. Panels (d),(e) show the spectral function for a disordered system, demonstrating the robustness of the zero modes. We took Jₖ = t, 2t in (b),(c) and Jₖ = 2t, Wₒ = t and Wₕ = 0.25t in (d),(e).

Fig. 2 : Spectral function of the effective non-Hermitian Anderson model. (a) The non-Hermitian effective Hamiltonian Eq. (4) stemming from the Dyson equation, where localized fermions (red) are coupled to delocalized sites (blue) with coupling strength γₖ. The spectral functions of the extended (b),(d),(f) and localized (c),(e),(g) fermions show the existence of zero modes. We took γₖ = t and Γ = 0 for (b),(c), γₖ = 3t and Γ = 0 for (d),(e) and γₖ = 3t and Γ = 5t for (f),(g).

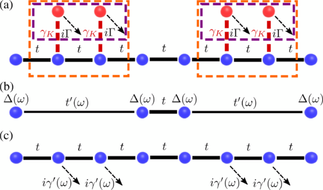

Fig. 3 : Schematic of the strategies to derive the effective Hamiltonian. Panel (a) shows two ways to separate the effective Hamiltonian Eq. (4) (dashed orange and purple rectangles). Panel (b) shows the effective Hamiltonian obtained from the dashed orange separation in panel (a). This model has a frequency-dependent hopping t’(\omega) and a uniform on-site loss \Delta(\omega), given below Eq. (5). At \omega = 0, it reduces to an SSH model with |t’| = t, which is known to host topological zero modes. Panel (c) shows the effective Hamiltonian obtained from the dashed purple separation in panel (a). This model has a frequency-dependent on-site loss i\gamma’(\omega) given below Eq. (6). At \omega = 0, it reduces to a model with non-Hermitian topological zero edge modes.

Horizons Ahead: From Robustness to Scalability

The implications are far-reaching. Systems based on many-body magnetism may be easier to fabricate, integrate, and scale. They could serve as foundational platforms for fault-tolerant quantum processors, resilient quantum sensors, and topological quantum networks.

Additionally, the correlation matrix framework opens new avenues for diagnosing, simulating, and controlling complex quantum systems. It may accelerate discovery across materials science, condensed matter theory, and quantum information.

As quantum technology transitions from promise to presence, one principle becomes clear: robustness is not a luxury it is a necessity. And the synergy between topology and magnetic interactions may prove to be its most solid foundation.

Conclusion: The Long Road to Quantum Realization

From Planck’s energy quanta to Shor’s algorithm, from trapped ions to topological zero modes, the journey of quantum computing is a story of theoretical vision, experimental persistence, and conceptual reinvention.

The Kondo lattice breakthrough represents not just a technical advancement it is a symbolic shift: a return to matter, interaction, and the computational power inherent in the fabric of nature.

The future of quantum machines lies not only in hardware and software engineering but in understanding the structural depth of physical reality itself. The quantum machine will be built not from bits alone but from the topological nature of existence.

References

Benioff, P. (1980). The computer as a physical system. Journal of Statistical Physics. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01011339

Feynman, R. (1982). Simulating physics with computers. International Journal of Theoretical Physics. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02650179

Deutsch, D. (1985). Quantum theory, the Church–Turing principle and the universal quantum computer. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspa.1985.0070

Shor, P. W. (1994). Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/365700

Grover, L. K. (1996). A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. STOC ’96. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/237814.237866

Preskill, J. (2018). Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum. https://quantum-journal.org/papers/q-2018-08-06-79/

Google AI Quantum and Collaborators (2019). Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1666-5

Lippo, C., Dauphin, A., Marino, R., Lewenstein, M. (2025). Topological Zero Modes and Correlation Pumping in an Engineered Kondo Lattice. Physical Review Letters, 134(11):116605. https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.116605

Microsoft Quantum (2023). Building a Topological Qubit. Microsoft Research Blog. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/microsofts-path-to-stable-and-scalable-topological-qubits/

IBM Quantum (2024). IBM Quantum Roadmap. https://research.ibm.com/blog/ibm-quantum-roadmap-2024

Comments